Ontario’s new Strong Mayor veto powers are controversial because they create the ability for minority rule: mayoral bylaws that are passed with one-third of council support.

It is no surprise that with no precedent, they are arguments regarding the mechanicisms of how mayors exercise their newfound powers.

There are arguments Mayor Andrea Horwath’s use of a Strong Mayor veto regarding the Downtown Stoney Creek parking lots should be quashed by the courts as ultra vires – beyond the powers granted to the head of council.

For those making these arguments, as the courts often write, redress for political decisions is ‘through the ballot box and not the courts’.

Related: I noted the debate regarding minority rule and local democracy at the end of my Feb column on the political consequences of a mayoral veto on this issue.

Bylaws Practically Immune from Judicial Review

Any court challenge of a municipal bylaw is limited to the questions of legality.

As the Ontario Court of Appeal wrote in Friends of Lansdowne Inc. v. Ottawa (City), “absent illegality, municipal by-laws are well insulated from judicial review. Section 272 of the Act prohibits a review of a by-law passed in good faith.”

“Thus, a court cannot interfere with an unreasonable by-law, but a court may quash one that is illegal.” [emphasis added]

Section 284.14 of the Act gives mayoral decisions similar immunity.

Further emphasising the ballot box is where political decisions are reviewed, not the court.

Let’s discuss the two parts of Mayor Horwath’s use of strong mayor powers:

1) the vetoing of the March 27 decision to not proceed with declaring the parking lots surplus to municipal need; and

2) the April 24 mayoral bylaw to declare the parking lots surplus.

March 27: Was There a Decision to Veto?

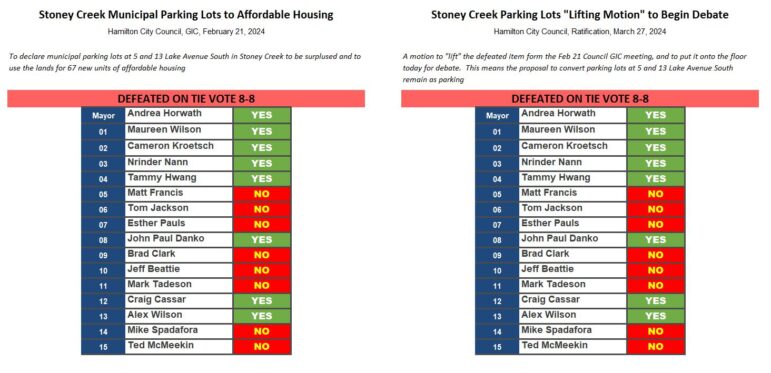

A motion to “lift” and debate the Downtown Stoney Creek parking lots matter failed on a 8-8 tie vote.

This raised the question: does the failure to lift an item constitute a decision by the Council?

In consultation with the City Solicitor, the City Clerk determined it was a decision.

The Municipal Act grants the City Clerk the power to make this decision, and they made it in good faith.

Legal Reasonableness of the Veto Implementation

Following this, Mayor Horwath vetoed “Item (g)(i)(1) of the Information Section in the General

Issues Committee Report 24-004” within bylaw 24-044.

Section 284.11(2) states: “If the head of council is of the opinion that all or part of a by-law that is subject to this section could potentially interfere with a prescribed provincial priority, the head of council may provide written notice to the council of the intent to consider vetoing the by-law.” [emphasis added]

Some argue the mayor cannot veto part of a by-law and that a veto must be of the entire bylaw.

Therefore, because Hamilton bundles most council decisions into a single confirming bylaw, the argument is that the mayor cannot exercise a Strong Mayor veto.

Reading the Act in this manner is not keeping with legislative intent.

Overriding localized opposition to housing is the clearly expressed reason the government created the strong mayor veto power.

Judicial Review Will Not Change Outcome

The role of the courts in a judicial review is just that, to review.

The Supreme Court of Canada directs reviewing courts to “remit the matter to the decision maker to have it reconsider the decision, this time with the benefit of the court’s reasons,” recognizing the “legislature has entrusted the matter to the administrative decision maker, and not to the court, to decide.” (Vavilov, paras 140 to 142)

If the Division Court were to adopt a technical interpretation on the mechanics of veto implementation, it would simply instruct the City Clerk to create a separate single-issue bylaw for the purposes of a mayoral veto.

The outcome will not change.

Different Municipal Act Sections and Legislative Intent

Council will vote tomorrow (April 24) on the Mayor’s bylaw to declare the parking lots surplus.

A letter to Council argues that the Mayor’s bylaw is illegal due to a conflict between sections of the Municipal Act.

284.11.1 states that the Mayor can propose bylaws under the Municipal Act “other than under a prescribed section.”

Section 270 states that municipalities “shall adopt and maintain” a range of policies, including “with respect to its sale and other disposition of land.”

The argument is that Section 270 constitutes a “prescribed section,” and no mayor may propose a bylaw related to policy matters unless explicitly provided for under Section 284.

“Prescribed section” generally refers to areas of the Act that specify how a municipality is to act, or restrictions on actions. i.e. how to fill vacancies on council, municipal bylaw enforcement, and sale of land for tax arrears.

The Legislature cannot predict every possibility, nor can legislation be written for every possibility.

Conflicts within legislation are common and resolved by determining legislative intent.

The Premier of Ontario has articulated that using available municipal lands for housing is a provincial priority, and his government specifically said Strong Mayor powers are intended to enable housing projects despite localized opposition.

The Act does not prescribe any requirements for how municipalities sell or dispose of their land.

There is an argument to be made; nonetheless, courts will be loath to quash a mayoral bylaw without clear and convincing evidence that Section 270 is intended to constrain Section 284.

Redress is at the Ballot Box

This brings us back to where we started.

As the courts often write, redress for political decisions is ‘through the ballot box and not the courts.’

Production Details v. 1.0.0 Published: April 22, 2024 Last updated: April 22, 2024 Author: Joey Coleman Update Record v. 1.0.0 original version